SPECIAL

REPORT 7 October 2013

Why are

Men of Prime Age

Missing

from the Labor Force?

by June Zaccone, Assoc. Prof.

of Economics (Emerita), Hofstra University and NJFAC Executive

Committee

.

The official unemployment rate fails to reveal

the full social burden that our slow recovery imposes on workers

and on our economy as well. This limitation is created by the

disappearance of millions of workers from the measure, which includes

only those not working but looking for work in the previous month.

The rate understates the level of unemployment because of the

shrinkage of the labor force participation rate

[LFPR], the fraction of the civilian non-institutional population

that is either working or looking for work. Those who are no longer

looking, among them, discouraged workers, are not counted in the

labor force. EPI

recently estimated that in August 2013, 1.66 million men age

25-54 were missing from the labor force. These would have been

working except for the recession.

"Certainly there's no shortage of supply;

demand

is the issue," said Bloomberg's Scarlet Fu about the

current low participation rate of prime-age men. The National

Jobs for All Coalition agrees: we believe that almost all people

of working age [with the exception of some people in school] want

to work. So when there is a precipitous decline in the participation

rate, we look for reasons beyond "unwillingness to work"

or "generous unemployment benefits." We'd like to know

how many of these "dropouts" are really discouraged

workers who have despaired of finding work.

What has happened to the LFPR of men is partly a consequence

of changes in the job market which have undermined their standard

of living, though it is not possible to determine how significant

those changes are to that decline.

While

unemployment is an ordeal for anyone, it still appears to be

more traumatic for men. Men without jobs are more likely

to commit crimes and go to prison. They are less likely to wed,

more likely to divorce, and more likely to father a child out

of wedlock. Ironically, unemployed men tend to do even less

housework than men with jobs and often retreat from family life...

The longer people who are currently unemployed remain out of

work, the more their skills will atrophy and the greater the

risk of a cohort of men—and women—who become permanently

detached from the workplace. Anything that raises employment

overall would help.

From close to 98% in early 1950's, the LFPR for

men in their prime work years [25-54] had plummeted to 88.3% in

August 2013.

LABOR

FORCE PARTICIPATION RATE, MEN 25-54

The situation of prime-age black men is even

worse [see below]. Starting at about 90% in 1972, when reporting

of these data began, down to 89% in 1979, then 87.5 in 1990. The

rate slipped below 84% in 2001 and slid precipitously from 2009,

ending in August 2013 at 80.6%, also close to a postwar minimum.

It is telling that the rate rose for both men of all races and

black men in the late 1990's, when jobs were relatively plentiful.

Labor

Force Participation Rate of Black Men 25-54

[Data availability for prime-age black men began in 1972.]

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I am dissatisfied

with the data available to find out why prime-age men have dropped

out of the labor force. The hypothesis I'd like to test is that

the major reason is the lack of decent jobs. However, this would

require an accurate count of discouraged workers, which we don't

have. Extensive periods of high unemployment lead to high numbers

of discouraged workers, who are excluded from both official unemployment

rates and the LFPR. Further, getting a count to add them back

in may be impossible. For example, the current measure of discouraged

workers includes only those who have looked for work within the

last year, not those who have been out of the job market for longer

than that.[1] Many former prisoners, disproportionately high-school

dropouts, would be among them, a larger group after the rising

wave of incarceration, which has only recently peaked. This undercount

is especially significant for black workers who have been most

affected by the war on drugs, as ex-prisoners have difficulty

finding employment.[2]

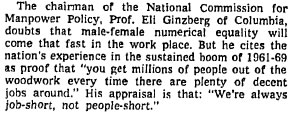

Even worse, some of the early retirement is likely

to be related to work discouragement, as is returning to school,

applying for disability payments, perhaps even exiting for home

care. How can we ever know how many people want jobs until we

are committed to providing a job for everyone who wants one, and

assisting those who need transportation, child care, or a work

place that accommodates a disability? The National Commission

on Employment and Unemployment (1979) decided against including

discouraged workers in the official unemployment count, on the

grounds that "during the upswing..., when opportunities for

work increase, many nonparticipants who are not classified as

discouraged workers also enter the labor force." In fact,

as the Chairman of another commission on labor policy noted, whenever

there are plenty of good jobs available, "millions of people

come out of the woodwork" to take them.[3] The following

analysis is necessarily based on these problematic data.

JOB AVAILABILITY

Looking at the trajectory of the LFPR above provides some support

for the effect of changing job availability. The rate started

sinking in the early 1960's, but the slide accelerated in the

1970's. What began at 96.0% in January 1970 was by December of

1979, 94.3. Further declines in the 1980's and 1990's ended below

90% in December 2008, with the ongoing recession, at least for

job-seekers. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Board conclude

that "analysis of state-level employment data indicates that

cyclical factors[that is, unemployment] can

fully account for the post-2007 decline of 2 percentage points

in the LFPR for prime-age adults (that is, 25 to 54 years old)."

However, their conclusion differs for its long-term secular decline.[4]

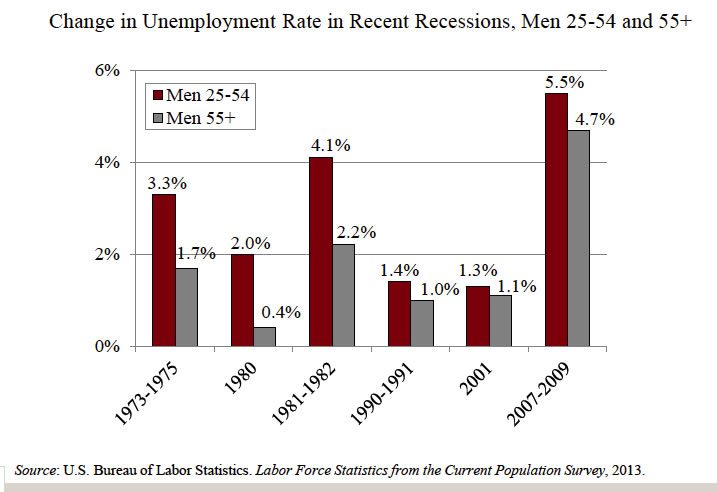

The aharp

change in the unemployment rate for prime-age men in the recessions

of 1973-5, 1981-2, and 2007-9 must have been a special shock [second

chart].

UNEMPLOYMENT

RATE, MEN 25-54 (seasonally adjusted)

0 0

Chart

below shows change in the unemployment rate for prime-age

men:

Per

Cent of Men 25-54 with Jobs

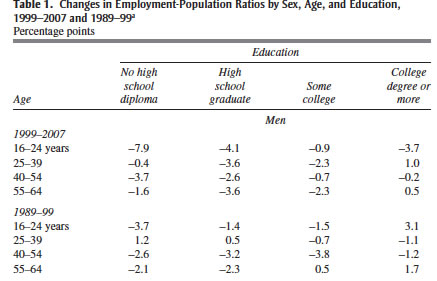

Job availability is limited, especially for those without college

degrees. However, though some jobs require college training, many

college graduates are doing jobs that could be done by those with

less training. This bumping occurs when jobs are in short supply.

The pre-crisis expansion of 2000-2007 was accompanied by the weakest

job expansion in decades. See also Missing Men in U.S. Workforce Risk Permanent Separation By Kasia Klimasinska, Bloomberg, Sep 18, 2014

This is not the inevitable result of globalization

and technology. It is the economic failure of public and private

sectors to create enough spending to put the available labor force

to work .

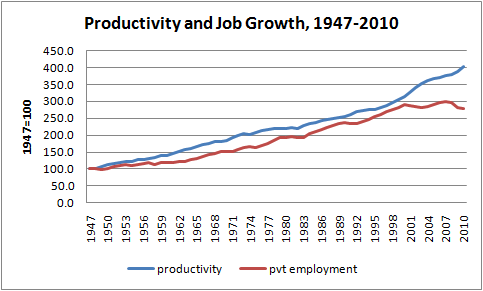

Jared

Bernstein depicts this failure:

He notes, "since the 2000s, when the split

in last graph begins, the U.S. economy simply hasn't been creating

enough demand to absorb productivity's growth. That been particularly

acute and evident in the recession, of course, but it predates

the downturn, especially, though not exclusively, for prime-age

men." Two MIT professors attribute this disparity to the

job-destroying

effects of advances in computer technology "in law, financial

services, education, and medicine." This may be true, but

whether we have full employment is a political decision. There

are still many tasks to be done, and should we ever run out

of these, we can take earlier retirement or longer vacations or

work shorter hours. The US still has an unenviable record as the

industrial country with

the longest average annual work hours in 2012, longer than the

UK, Australia or Japan, not to mention Scandinavia, and above

the OECD average, which includes Estonia, Mexico, Turkey and other

poorer countries.

Josh

Blivens concludes, "We noted a long time ago that policymakers

seemed to have largely given

up on presenting actual solutions to the jobs-crisis. 2013,

however, is the first year that federal policymakers have succeeded

in setting policy to actively

make it worse, and stomping on some of the first

promising trends in years."

OTHER REASONS FOR THE DECLINE--retirement,

disability, home responsibilties, education, and other

RETIREMENT

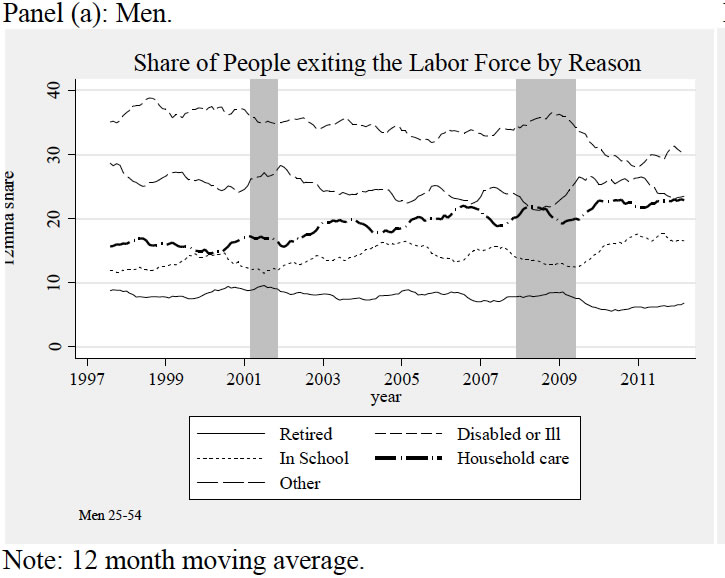

THE GOOD NEWS Some of those men

who can't get work retire. In 2012, about 8% [see graph below]

of men 25-54 who left the labor force retired. These men are unlikely

to return when employment improves. Many men who lose jobs in

their 50's can't find another, and are forced to retire. However,

a very small share of this labor force decline is a good sign,

one that indicates that for some few men, there is a financial

possibility of withdrawing from the labor force before old age.

Some workers with a 30-year work life might have started at 18

and be eligible for retirement benefits when they are about 50

years old.

This choice is unlikely for the majority of those

who have withdrawn, and will become even less likely as younger

workers lose the right to employer-provided pensions, especially

those that provide a defined-benefit.

Since 1967, the BLS, through the

Current Population Survey, has asked those who are not in

labor force the reason for their absence. Researchers,

using these data, examined the responses of only those

who were employed or unemployed the previous year, and

so more likely to return.

Source: “A

Closer Look at Nonparticipants During and After the Great

Recession,” by Julie L. Hotchkiss, M. Melinda Pitts and

Fernando Rios-Avila. Working paper 2012-10, 8/12, Federal Reserve

Bank of Atlanta.

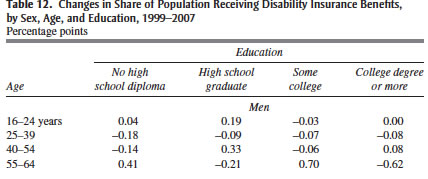

Illness and Disability

"Labor force participation among prime-age

men has fallen for two main reasons: increased access to Social

Security disability benefits and decreased demand for less-skilled

workers." These are related. As the relative wages of high

school dropouts have declined, disability

benefits have replaced a larger fraction of earned income.

[5] We'll see that this can be debated.

Probably a majority of researchers attribute

the secular decline of the prime male LFPR in part to the availability

of Social Security Disability Insurance. "Expansions

in the...program account for a substantial portion of that decline,

because most individuals who start receiving disability benefits

never reenter the labor force; increased incarceration rates

also appear to have played a significant role. However, those

trends appear to have subsided over the half-decade prior to the

Great Recession...."

The graph above includes only men 25-54. Unfortunately,

it is much harder to read than the one for all workers of that

age, show below under Other.

Some of the evidence used to point to the role

of Disability Insurance is interviews with those who have left

the labor force, as noted above. A plurality of men age 25 to

54 who left the labor force over the last 15 years said they did

so because they were ill or disabled [[about 30% recently:

top line of graph]. Autor

and Duggan point to two changes which encouraged this move:

in 1984, the disability determination was liberalized to cover

depression and severe pain, reversing a major reduction in

numbers on disability. The second occurred because of a rising

replacement rate: disability benefits are both progressive and

indexed to the mean wage. Over the next decades, the ratio of

disability payments to wages rose as the pay and job prospects

of unskilled workers deteriorated. The disability program also

includes Medicare.

Others disagree. "Some of the youngest and

least skilled groups have seen increases in receipt [of disability

insurance], but the

magnitudes are tiny compared with the declines in the employment-population

ratio... ". [6] Or, "after the mid-1990s, we

find little role for the DI program in explaining the continuing

employment decline for men with work limitations."

Other analysis "suggests that other factors

were behind that decline in participation, and that the

growth in D[isability] I[nsurance] rolls experienced in the 1990s

was made up of men who would not have been working regardless

of the DI expansion."

It is also evident that this rate rose with

the recession and has fallen since, as the job market slightly

improved. Research has shown the relevance of job availability:

"The

largest declines [in the LFPR] have occurred in states with the

largest job losses. ...during the downturn and recovery periods

of the recessions of 1981–82, 1990–91, 2001, and 2007–09."

Household Care[graph above]

Though workers with family members who are sick

or otherwise need care face a limited set of options in the US,

it is good news that men are taking on this role in greater numbers

[above, third line up]--rising from 16% of those leaving the labor

force in the late 1990's to about 22% at the end of 2011. Women

continue to have the major burden. This category for both men

and women [the orange line in the graph below, right-hand axis]

included about 47% of all those leaving the labor force in 2011.

Back to School [graph above]

Roughly 17-18% of prime-age men who left the

labor force returned to school [graph above, second line up from

bottom]. Though the upward shift after the recession was most

pronounced for those

with some college or a degree, the shift occurred at all levels

of education. Presumably these men plan to return to work

once they finish schooling and/or find a job.

Other [graph above]

About 22% left for a variety of reasons. They are in the BLS

category of "not in the labor force/currently wants a job." This

would include those who lack transportation, child care, or an

undefined reason, "although

this category may be capturing some of the discouraged workers...

In April 2012, these people accounted for only 1.1 percent of

all nonparticipants (41 percent of the marginally attached—those

who want a job, are available to work, and searched in the previous

year)"

Shaded areas are periods of recession; the right-hand axis measures

the category of those leaving to care for members of their household.

NOTES

[1] "In 1994, the

BLS changed the way in which it counts 'discouraged' workers.....

If one is unemployed for more than 52 weeks, even if one continues

to look for employment, one is dropped from the labor force."

"Between one and two million jobless workers who gave up

their job search after twelve months of frustration are no longer

counted in official figures."

[2] "At

2001 rates, 6.6% of the population and 17% of men will be incarcerated

in State or Federal prison during their lives..." "Incarceration

disproportionably affects males under 35, African Americans, and

the low educated." "...the share of white male school

dropouts who had ever been incarcerated rose from 14.4 percent

in 1999 to 28.0 percent in 2009; the rate for black male dropouts

rose from 46 percent to 68 percent." http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall

2012/2012b_Moffitt.pdf

[3] Helen Ginsburg, Full Employment and Public

Policy: the US and Sweden, Lexington Books, 1983, pp.30-31.

She quotes from A.H.Raskin, NY Times, 2/15/76:

[4] "Expansions in the Social Security Disability

Insurance program account for a substantial portion of that decline

[of the prime-male LFPR from 1940's to the 2000's], because most

individuals who start receiving disability benefits never reenter

the labor force; increased incarceration rates also appear to

have played a significant role. However, those trends appear to

have subsided over the half-decade prior to the Great Recession;

that is, the LFPR for prime-age males was stable at around 90.5

percent from 2003 to 2007." http://www.bostonfed.org/employment2013/papers/Erceg_Levin_Session1.pdf

[5] "Many

prime-age men who leave the labor force during downturns stay

out even after the economy recovers, although not to the same

extent as teenagers. The weak cyclical recoveries of the

labor force participation rate of prime-age men are related to

a secular decline."

[6]

|